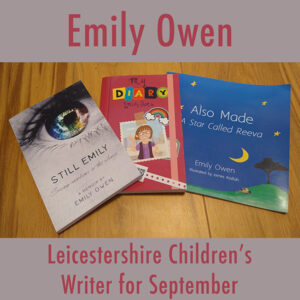

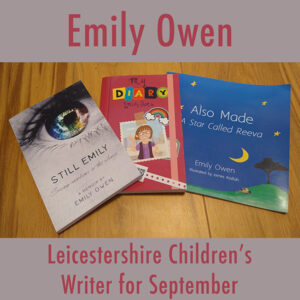

Emily Owen is the show’s Leicestershire children’s author for the month of September. She is an author who deals frankly with faith, serious health conditions, doubt, family life, and personal growth.

Emily has dealt with Neurofibromatosis Type 2 for most of her life, and the surgeries required to save her life have taken away her hearing and some of her other nerve functions. Despite this – or perhaps because of this – she has developed into a writer with a strong voice that delivers the unvarnished truth in a way that is both poignant and motivating.

You can learn more about Emily at emily-owen.com. Her book Also Made: A Star Called Reeva is a Christmas story for children of all ages. My Diary is a thought-provoking memoir good for older children and young teens, and Still Emily is an autobiography best suited for teens and adults.

Full Transcript of this Episode:

This episode of the Children’s Literature Podcast is brought to you by the last berry picking of the year. The last berry picking of the year – you won’t know it happened until there just isn’t another one.

Welcome to the Children’s Literature Podcast. I’m your host, T.Q. Townsend. This episode is about Emily Owen.

Each month this year I am featuring a children’s writer from Leicestershire, and in September I am delighted to tell you about Emily Owen, an author who makes the expression “take lemons and make lemonade” seem like the understatement of the century.

Before we get started, I’d like to remind everyone that we are just 7 episodes away from our 100th show, in which co-host Chloë and I will answer your questions. I have some good submissions, but I can squeeze in just one or two more. If you have anything you want to ask us, send it in to letters@childrensliteraturepodcast.com.

I also want to hear from listeners for an upcoming episode on Stig of the Dump by Clive King. This is a book that isn’t much known in the United States. I had never even heard of it until about a year ago. It’s a fun, wacky tale about some kids who find a real caveman living in their local dump. Or . . . is he real? I seem to have discovered that British people absolutely love this book, and they have different theories about whether or not Stig is imagined by the children, or if he’s an actual caveman left over from prehistoric times. I want to do an episode where I share your theories about Stig. Is he real? Is he imaginary? Is he a time traveler? Is he a modern kid who is pulling a prank? You can send in audio or written answers via Instagram – the account is @childrensliteraturepodcast, or they can come in to the email address, letters@childrensliteraturepodcast.com. I think this episode will be fun, and I am open to any theory, whether it’s rational or completely out of left field.

Emily Owen was born in 1979. Her home was in Leicester City, where she was the oldest of four sisters in a home she described as “fun, chaotic, noisy, supportive, and faith-filled.” She grew into an intelligent and talented teenager, with rare combination of being very gifted both in athletics and music. She played the piano, flute, guitar, and accordion and ran cross country. She was voted Head Girl by her peers at school. But she also seemed to have sudden and uncharacteristic bouts of dizziness. From time to time, Emily would suddenly get dizzy and lose her balance, occasionally injuring herself. It was very easy to dismiss these moments as just common childhood accidents, but in hindsight they were terrible warning signs. She would get terrible headaches from time to time, which were diagnosed as migraines, but no migraine medications seemed to help.

By the age of 16, Emily’s headaches and dizziness were so bad, and her GP was so flummoxed by the way her symptoms defied any treatment, that she was referred to a neurologist. After some alarming test results, it became clear she needed urgent treatment for a very rare and very serious condition. You’ve probably never heard of Neurofibromatosis Type 2. It’s a genetic condition that causes tumors to develop on the skull and along certain nerves such as those that enable hearing. Emily’s promising future was upended by the sudden discovery that her dizziness, headaches, difficulty walking, and balance problems were caused by the presence of two brain tumors that were putting pressure on her brain. They were so large that it wouldn’t be safe to operate on them until doctors had given her large doses of steroids.

Emily’s path from this point was incredibly difficult. She went from the life of a promising, talented, hardworking teen to a kid fighting for her life as she was shuttled from hospital to hospital, enduring multiple operations and near misses with death. Summarizing her story seems kind of crass, now that I’m telling it, because it’s not possible for me to properly convey just how much she went through and just how resilient she is.

Emily’s life may have taken a drastic turn away from what she had planned for herself, but it’s not surprising that someone with so many talents was able to adapt and reconfigure. She’s since become an author and educator. Her Christian faith is deeply important to her, and this is reflected in the several books she has written on biblical themes, which are naturally targeted at adults interested in Christianity. But she’s also written three books that children would really enjoy.

Still Emily is a memoir that is best left to older teenagers. It’s perfect for this age group as it’s not too long to read, but still manages to tell a full story of Emily’s diagnosis, treatment, and ability, through it all, to remain still Emily. The author is remarkably unflinching in her description of what she’s been through. The surgeries required to save her life have left Emily Owen deaf, a particularly cruel stroke of fate for a musician. They also damaged her facial nerves, making it difficult for her to have normal facial expressions and speak as clearly as before. I can’t imagine being just out of my teen years and having to deal with those kinds of struggles, and I think teen readers can really benefit from how clear eyed Emily Owen is about the fact that sometimes, life is painfully, irrationally unfair.

And yet the story also shows how normal life somehow manages to go on in such situations. I loved a passage early in the book, when Emily was forced to stay at home on bed rest before an operation. A package arrived at her house, and inside was a mix tape. It had not only meaningful songs, but also the latest news from school and warm wishes from her friends. Emily Owen is about my age, and those of us who grew up in the 90’s will remember fondly how personal and special it was when someone gave us a mixtape. I can only imagine how much more special this one was because it came from several people wanting to remind her that she was still part of a circle of friends.

The memoir is a mix of extremely relatable moments, such as going down to London for a special night of musical theater, as well as painful, surreal memories like spending an entire night listening to music before a surgery that will render Emily completely deaf. She describes having a “bucket list” for her sense of hearing. I have to admit that as someone who has been heavily involved in music my entire life, these parts were very difficult to read. But Emily’s total lack of fear in describing what she went through is what makes her memoir so raw and real and compelling.

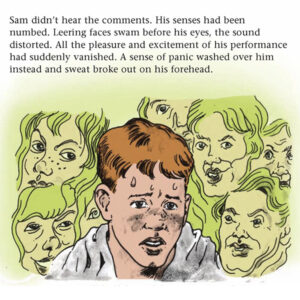

Still Emily would be a bit much for younger readers, which is why it’s so great that Emily Owen replicated her story in a format better suited for tweens and young teens in My Diary. This book is written in the format of a journal, covering a lot of the same material as Still Emily but in a way that younger readers will be able to understand. However, it still has the same unflinching realism. One of the title pages warns “This diary is about real life. Sometimes sad things happen.”

That statement could be seen as needlessly harsh, but I feel that it’s a very useful thing to say to kids who are growing out of childhood into their teen years. I can’t think of a better way to prepare children for real life than to say “sometimes sad things happen.”

Emily Owen’s religious faith is a huge part of her life, but one of her skills as a writer is to frame her faith in a personal way. This means that if you are a Christian, as she is, her beliefs will resonate powerfully with you. It also means that even if you aren’t a Christian, her personal experiences will resonate powerfully with you. She writes about her faith in a way that is real and humble and relatable. I really appreciated this passage from My Diary that captured what it feels like to have your worldview shaken hard by a trying experience:

I think this is the worst situation I’ve ever been in . Worse than being bullied, worse than sitting in A&E, worse than everything put together. Lying here, staring at the ceiling, I remember all the times Mum has said to me, “let’s pray about it.” It’s always the first thing we do. OK, I can still pray.

“God? God?”

Sometimes people say they feel that their prayers are bouncing off a ceiling, which means they don’t feel like they are getting through to God. I always used to think, ‘I Don’t know what you mean.’ But now I do know.

Whether you are Christian, of another faith, or of no faith at all, I think you can find this passage completely relatable.

In this moment, Emily is a girl having to deal with major surgery, which carries its own frightening risks. She is also about to have her sense of hearing taken away, which is especially punishing for someone who loves music so much. I think most people would feel terribly alone at such a time.

It takes a lot of courage to acknowledge a moment of fear and solitude. It would be so easy to just say what fellow believers expect, but Emily Owen chooses to be honest. I have very deep respect for anyone who chooses to acknowledge moments of fear and doubt rather than tell comforting lies that paper over moments of trial and tribulation. I think that young readers could learn a lot from Emily by reading My Diary.

Emily Owen’s third book which is good for young readers is Also Made. This is an illustrated book which can be understood by all ages. It is a Christmas story, in the theological sense, but it’s still endearing enough to have wider appeal if you are familiar with the Christmas story. A fairly ordinary star, Reeva, doesn’t feel terribly special, but he learns that he has a greater role to play as one day he discovers that he is the star of Bethlehem shining over the stable where baby Jesus was born.

The book’s one weakness is that the illustrations don’t do much service to the good writing, but I think if it’s read by a good storyteller, illustrations won’t be needed. The story’s final message is that you don’t need to have stereotypical gifts in order to be important or useful. Whoever you are, and whatever your gifts are, you’ll have something to offer the world as long as you are willing and ready when the chance comes along.

The work of Emily Owen is unapologetically infused with faith and unflinching in its description of pain and progress. Her stories have a lot to offer young people. Both Still Emily and My Diary help to build a sense of empathy, but without ever triggering a condescending sense of pity. There is no varnish on experiences based on fear, confusion, and pain, but this isn’t done for shock value. It’s just raw and real and honest.

You can learn more about Emily Owen at emily-owen.com. In the interest of making this episode accessible to those who are deaf or hard of hearing, I’ve also published a full transcript of this episode at childrensliteraturepodcast.com, and I will try to do this as much as possible in the future. Whether your approach to Emily Owen’s writing is faith based or secular, you will sincerely come to appreciate her honest, open voice as she speaks about her very personal experiences with a disease that only affects one in 60,000 people. She has a powerful voice and experiences that can teach even the most world-weary reader, and Leicestershire is lucky to claim her as a local writer.

You’ve been listening to the Children’s Literature Podcast. Please subscribe and give the show a rating. Send comments to letters@childrensliteraturepodcast.com. I’m your host, T.Q. Townsend. Thanks for listening.