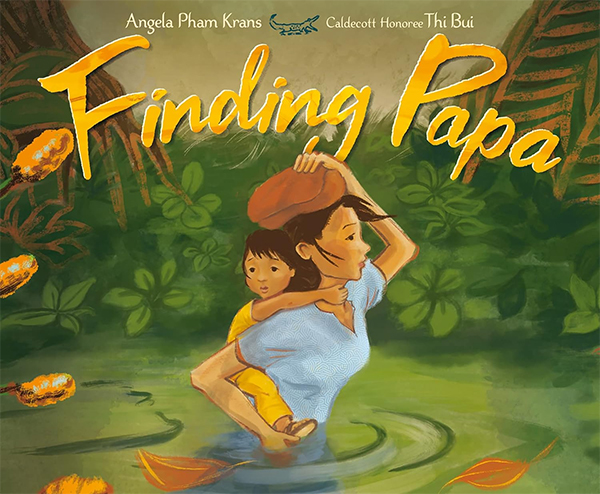

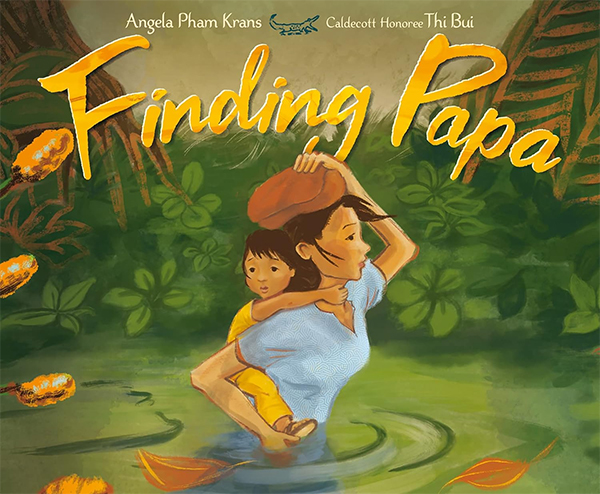

Angela Pham Krans is the author of Finding Papa, a beautiful and touching tale about Mai, a little girl whose father has to say goodbye for a while when he leaves to find a new and better home for the family. Eventually Mai and her mother make a dangerous and daring journey by boat to rejoin Papa in their new home in America.

This story, which is beautifully illustrated by Thi Bui, is based on Angela’s experience as one of the many Vietnamese people who fled their homeland in the wake of the Vietnam War. In our conversation, we discuss the effect that Finding Papa has on readers of different ages, why Angela chose to focus the plot on one family rather than the larger historical and political context, and where she got the inspiration to give the main character a pet chicken.

Finding Papa has recently been placed on the American Library Association’s 2024 Notable Books list. Angela has also recently published Words Between Us, a charming story about how an English speaking grandson learns to communicate with his Vietnamese speaking Grandmother. You can learn more about Angela and her work at angelakrans.com and follow her on Instagram at angela.pham.krans.

Activity: The Geography of the Boat People

While younger kids will be able to appreciate Finding Papa for its moving story about family reunification, older children can use this book as a starting point for exploring how the Boat People left Vietnam and made new homes all over the world.

Have students locate Vietnam on a map. Ideally, provide an outline map of the world that they can draw on. Have students research the different routes that refugees took out of Vietnam during the 1970’s and 1980’s. Try to discover which countries most of them traveled to and in what numbers, as well as estimates of how many of the Boat People did not survive their journeys. If it’s difficult to know exact numbers, try find out why. Students can label the map with differently colored arrows labeled to show how many people went from Vietnam to each new country.

Activity: The History of the Boat People

There were many reasons that people decided to leave Vietnam during the 1970’s and 1980’s. Students can research the history of this country during this period and present a written report or give a presentation about the reasons people chose to leave, and what drew them to the new countries they arrived in.

Activity: Mai’s Mother Keeps a Journal

Finding Papa focuses on Mai, a very young girl, who is taken on a dangerous but hopeful journey to a new home. But what must her mother have been feeling? Students can write journal entries from the point of view of Mai’s mother. Entries might include describing the decision for Papa to go ahead of the family to prepare the new home, the first night without Papa, a night on the boat after the storm, the first night after being rescued, or any other part of the story. Encourage students to imagine what it would feel like to be a young woman with a toddler on such a journey, and to express these emotions in the journal entries.