I’ve just seen the documentary Butterfly in the Sky, which is about the public TV show Reading Rainbow. This show, which was hosted by LeVar Burton, helped millions of kids, including me, to understand just how magical it was to take a look in a book. Watch me try not to get choked up as I tell you about my favorite moments in this documentary. Also, I have a little idea regarding the theme song that I hope some of you will be interested in . . .

Category: Episodes

135 – Sold A Story Episode 10

Emily Hanford is back with Episode 10 of Sold a Story. I wanted to take some time to listen to this one several times and think about it before responding, because it addresses some very serious challenges in the literacy wars.

Some people who were confronted by the failings of Balanced Literacy — the highly profitable but thoroughly unscientific school of thought pushed during the last few decades — were unable to accept new information, and have clung to their old, ineffective ways of teaching. Why? And how can we move forward without replacing one evangelical movement with another one? Follow along on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/childrenlisteraturepodcast Check out more episodes of the show: https://www.childrensliteraturepodcast.com

134 – Politics in Anne of Green Gables

Politics? In a story about a young teen girl from a tiny town in Canada’s smallest province from over 140 years ago? Actually, yes! Politics come up frequently in the classic novel Anne of Green Gables by Lucy Maud Montgomery, and they have some surprising things to say to modern readers, most importantly that we don’t have to let differences of opinion drive us apart.

This is the second to last installment in my series on Anne of Green Gables as a work of historical fiction. Hopefully it can help you think of ways to use Anne’s awakening to a wider world beyond the small village of Avonlea to start interesting conversations with your own kids about why people have such different views about how the world should be run, but also that we can be good friends with members of different political parties.

Activity: Kitchen Politics

In Anne of Green Gables, Anne asks Matthew questions which show that she is starting to become aware of a larger world. He understanding of politics is very limited, though, and is very naturally rooted in wanting approval from Matthew. She expresses support for the Conservative party when she learns that’s how Matthew votes, and her enthusiasm is reinforced by the fact that her school rival Gilbert supports the Grits.

This passage is a great lesson for both parents and children. Matthew doesn’t ever try to lecture Anne or tell her what to believe. He just listens and answers her questions (or, at least, responds as well as he can). Kids can also pay attention to Anne’s biases. She doesn’t actually support the Conservative party because she knows nothing about the policies they favor. She does seem to be paying attention to things adults say, though, as she relays Mrs. Lynde’s views on educational policy and votes for women. Encourage children to watch out for these kinds of biases as they become aware of the larger world. They should never support a political party because it happens to be the tribe they’ve landed in; rather they should engage with and work to understand the ideas and policies of political parties so that they can be confidently informed about the platforms and candidates they support.

In your discussion, don’t forget to point out that although many of the characters in Anne of Green Gables belong to different political parties, they are still friendly, respectful, and neighborly toward one another. Different points of view are helpful in figuring out which policies will be best and challenging bad policies. These differences are not the most important thing in life and do not mean people can’t be good neighbors and friends.

133 – St. George and the Dragon

We went to the St. George’s Day celebrations in Leicester City to have some fun and learn a little bit about the very ancient story in which St. George slays a dragon to save a city from its really, really bad breath. Hear the original tale and find out why it still has good ideas to teach children today, even if it is very ancient and unfamiliar in some ways.

Are the parents in the story terrible? Why is St. George so cool? And what does this story have to do with Taylor Swift?

Translation of Chapter 56, “”De Sancto Gerogio” from the Legenda Aura: Vulgo Historia Lombardica Dicta by Jacobus de Voragine

by T.Q. Townsend

George was a Roman soldier originally from Greece, who arrived in a city named Silena, which was in the North African province of Libya. Next to the city there was an enormous lake, and in it lurked a horrible dragon. Anyone who was foolish enough to attack the dragon would just end up running away . . . or being eaten. The dragon’s breath was so foul that whenever it came near the city, anyone who breathed it would be infected and fall down dead.

To keep the dragon from coming to the city and killing everyone, the people would put two sheep outside the walls every day. But pretty soon, the people of Silena started to run out of sheep. So they started putting out just one sheep, and a child. They drew lots to see which sons and daughters would be given to the dragon, but soon enough only one child was left: the only daughter of the king.

At first the king refused to give up his beloved daughter, saying, “Take away all my gold and silver, and half my kingdom, but don’t take my little girl!” Well, then the townsfolk were pretty annoyed, and they shouted back:

“Look, King, why are you offering to give up your gold and silver now, after all of our children are dead? How come you only want to save YOUR daughter? Unless you give your daughter to the dragon like everybody else, we will throw you in your house, lock the door, and set it on fire.”

The princess then began to weep, and the King turned to his daughter, saying, “Alas, my sweet little daughter, what shall I do? What shall I say? I had hoped to see you grow up and get married one day.”

Then he turned to the people and said, “Can I have eight days with my daughter to say goodbye?”

The people said, “Well, all right.”

After eight days had passed the people came back in great anger, saying, “That dragon’s breath is LITERALLY killing us. Why are you letting us die just to protect your daughter?

Then the king saw that he could not save the princess. So he gave her fine royal robes to wear. Then he threw his arms around her and with tears running down his face said, “Alas, my sweetest daughter, I thought that one day I would be able to hug your children and help look after them as they grew up, but now you are going to be devoured by a dragon. Alas for me, my sweet darling. I would have invited great princes to your wedding, given you a palace decorated with pearls and filled with the music of drums and organs. But now you go to be devoured by a dragon.”

The king kissed her one last time and then let her go, saying, “Oh, my daughter, I wish I had died before this day so that I did not have to lose you like this.”

Then the princess fell at her father’s feet and asked him for a blessing. Her father blessed her with many tears, and then the princess bravely made her way to the lake. Just then George happened to be riding by, and when he saw the weeping girl he asked her what was wrong.

The princess only answered, “Noble young man, get on your horse quickly and get out of here, or you will die with me.”

But George answered, “Don’t be afraid, little one, but tell me, what are you doing here with the entire city watching?”

She replied, “I can see that you are a kind young man with a magnificent heart, but you really need to get out of here. Do you wish to die with me?”

But George refused to go, saying, “I won’t leave until you tell me what’s going on.”

The princess told her tale, and when George at last understood the situation he said, “Little one, don’t be afraid, for I will help you in the name of Christ.”

The princess replied, “You are a good soldier, but you should hurry and save yourself. Don’t die with me! I am already going to die, and if you try to save me you’ll just die too!”

And while the princess and the knight were speaking – behold! The horrible stinking dragon raised its head from the lake. The princess began to tremble and said, “Run away, my good lord! Run away fast!”

But George mounted his horse, made the sign of the cross to give himself courage, and boldly attacked the dragon as it charged toward him. He swung his lance mightily and trusted his soul to God. The knight and the dragon collided. George wounded the dragon grievously and threw him to the ground. The dragon was defeated, and now cowered at his feet like a tame dog.

George brought the dragon back to the city, and at first everyone began to head for the hills, saying, “Oh no! We’ll all die!”

But George called them back, saying, “Have no fear, for I was sent to you by the Lord to save you all from the dragon’s punishments. All you have to do is believe in Christ and be baptized, and I’ll kill this dragon.”

The King and all the people thought that sounded fine, so George killed the dragon with his sword and ordered it to be carried away from the city. Twenty thousand men and their families were baptized that day. The king offered an enormous pile of money to blessed George, who instantly refused and said it should be given to the poor. Then George instructed the king to take good care of churches, honor the priests, pay attention during church services, and always look after the poor. Then he kissed the king and left.

The End.

Oh, though in some books telling this tale it says that George killed the dragon before he told everyone to get baptized. Which I have to say seems a bit better to me.

132 – “Lancelot and Elaine” in Anne of Green Gables

Tennyson’s poem “Lancelot and Elaine” plays a huge part in the plot of Anne of Green Gables by Lucy Maud Montgomery. Anne and her friends decide to act out the scene where the Lady of Shalott dies and floats downriver to Camelot, where the court of King Arthur mourn her. However, Anne learns the hard way that life is more hilariously imperfect than the romanticized fictional world she admires so much.

Find out more about this poem and why it was such a big deal in the 19th century, inspiring painters to revisit the subject of Elaine of Astolat over and over again. You’ll also learn that, although fads themselves change, teenagers really don’t. Anne and her friends would have had feelings about this poem that are very similar to how teens today feel about their own popular culture.

131 – “Bingen on the Rhine” in Anne of Green Gables

Anne of Green Gables features a LOT of poetry. The book is set in the 1880’s, and back then teenagers would carefully select poems to recite to one another in the way that teenagers a few decades ago used to select songs to include in a mix tape.

“Bingen on the Rhine” is a beautiful poem by Caroline Norton, a writer and women’s rights campaigner who is so fascinating in her own right that her story could fill a hundred books. Gilbert Blythe chose to recite her poem in front of Anne Shirley – and every other kid at school – because it was one of the only ways he had to express to her his deep regret at having offended her, and his deep hope that she might one day forgive him.

Activity: Caroline Norton

Caroline Norton was a very important figure in the early battle for women’s legal rights. She was trapped in an unhappy marriage to a cruel and controlling man, who confiscated the money she earned from her writing and kept her own children away from her. She worked hard to raise this issue with the British parliament, which eventually passed laws that granted women the same legal rights as men when it came to property ownership, divorce, and child custody.

Students can research Caroline Norton’s life and the important social and legal reforms she worked so hard to achieve. It’s especially important for them to understand how these early efforts made the later campaign for women’s suffrage possible.

Activity: Memorize and Recite a Poem

Students can select a poem to research, memorize, and perform for others. The poem could be serious or humorous. It could tell a story or be more abstract. Poems should be selected to convey a special meaning to the audience. After the performance, have students ask audience members if they can guess the reason the poem was selected.

130 – Sold a Story is BACK!

BOOK DRAMA ALERT! The podcast Sold a Story is back after more than a year. This show did some great reporting on just why so many American kids aren’t learning to read – and which literacy gurus and for-profit publishers are behind the problem.

I had to put out a quick response to this episode because I truly believe this show is that important. This is journalism at its finest – investigating real problems that affect ordinary people. Find out what I noticed in this episode, especially why this whole thing looks more like a religious scandal than an ordinary education debate.

I’ll keep reviewing future installations of Sold a Story, letting listeners know what I think about how parents and teachers can advocate for better literacy education for children.

129 – THE JUVENILE DELINQUENCY PODCAST

THIS IS NO LONGER THE CHILDREN’S LITERATURE PODCAST!! BECAUSE READING IS FOR LOSERS!!!! THIS IS NOW THE JUVENILE DELINQUENCY PODCAST!!! LISTEN HERE OR WATCH ON YOUTUBE. OR DON’T. WE DON’T CARE!!!

IN THIS EPISODE, FIND OUT THE BEST WAYS TO KICK PEOPLE, HOW TO CRIME BETTER, AND WHY BEING RUDE IS THE BEST!!!!!!!

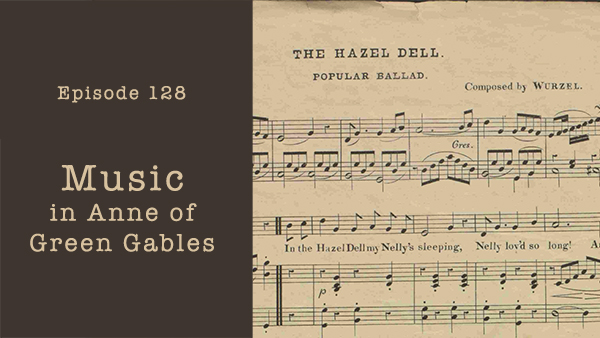

128 – Music in Anne of Green Gables

Lucy Maud Montgomery carefully reconstructed the pop culture of the 1880’s when she wrote Anne of Green Gables including the music that teenagers were wild about. While singing is referenced dozens of times in the book, just three songs are actually named, and they were all real songs!

Activity: Learn one of Anne’s Favorite Songs

Three songs are named in Anne of Green Gables, and they were all popular sentimental ballads. You can find the sheet music for these songs online in the following archives:

“Nelly in the Hazel Dell” by George Root (using the pseudonym Wurzel)

“Far Above the Daisies” by George Cooper and Harrison Millard

“My Home on the Hill” by W.C. Baker

Learn one or more of these songs and have a performance! You could try to re-create the song as it is performed in Anne of Green Gables, or you could reinterpret it in your own style.

127 – Greta Gerwig Isn’t Right for Narnia

The Chronicles of Narnia are getting the Netflix treatment, and I hope that they’re great. I hope they help an entire new generation of kids discover one of the best book series ever written. But I’m not encouraged by the appointment of Greta Gerwig as the director, because she’s proven twice now that if she’s handed a property made for children, she’ll make a film for adults.

You can listen in your usual audio feed, and there’s also a video version of this episode:

What do you think? Are you optimistic or pessimistic? What things do you think a filmmaker like Gerwig will do right and what will she do that messes around too much with the source material? And which adaptations of the Narnia series are your favorites?