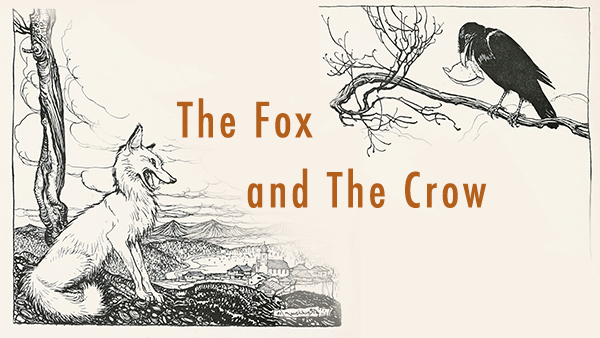

“The Fox and the Crow” has one of Aesop’s most useful lessons: don’t trust a stranger who comes along with flattering words, because there is a good chance you will regret it! This tale is thousands of years old, but it’s been retold over and over, from the medieval legends of Chanticleer the Rooster and his foe Reynard the Fox, to the Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer, to a well-loved modern tale — “The Gingerbread Man” which was first published in America in 1875.

Check out the video version of this fable, which is accompanied by charming vintage illustrations of the tale.

Activity: Identifying Danger

Children need to learn how to be safe in public and online, but it’s best to teach this in a way that doesn’t frighten them or make them needlessly wary of others. By telling the story of “The Fox and The Crow” children can see an example of how someone who was untrustworthy got the better of another person who was too eager to be flattered. By using this animal tale, discussions about safety can seem less personal and less intimidating.

After reading “The Fox and The Crow” together, you can have a discussion on a relevant topic of safety. For example, children should be wary of giving away information about themselves online. Websites may look like just a bit of fun, offering silly quizzes or games for free, but these are in fact ways to gather personal data such as names, birthdates, addresses, and other information that could be used for identity theft or credit fraud. In these cases, the websites are the Fox, and the children need to be wiser than the Crow, recognizing that they should not give away important information just because the website asking for it looks like a bit of fun.

This fable can also be used to talk about why children should avoid adults who seem overly friendly, especially if they are strangers. Adults who are not safe to be around will sometimes pretend to need help from children, or offer kind and friendly words. Unless a child knows that grownup, and has been told by a parent that it’s ok to listen to them, the stranger should be thought of as a Fox and avoided.